In November we were pleased to record a conversation between three educators, Daemin Whetung, Alan Macdonald and Sian Nalleweg, about how they use a land-based learning approach to teaching students about food systems. The facilitation was led by Robbie Knott from Alderhill, an Indigenous owned and operated planning firm in BC.

Daemin Whetung is a mother of two with another one due last December. Daemin has been raised learning, working and loving wild rice, taught to her by her dad James Whetung who is the dreamer and founder of Black Duck Wild Rice. She believes that “connection to the land” has been disrupted for many people and hopes to help people reconnect to the land and water through wild rice and her experience with it.

Alan Macdonald teaches grades 7 and 8 in an enrichment program, Challenge North, at Loughborough Public School. Increasing food literacy, addressing climate change and finding opportunities for reconciliation have been motives behind his school’s recent projects, such as seeking a salad bar grant from Farm to School Canada, school composting program, raised garden beds on site and support of a large food bank garden within the community, as well as creating wampum inspired artwork in collaboration with Indigenous community members and Indigenous cultural spaces on school property. His school is very excited to be building a teaching kitchen and greenhouse this year to extend opportunities for students around food.

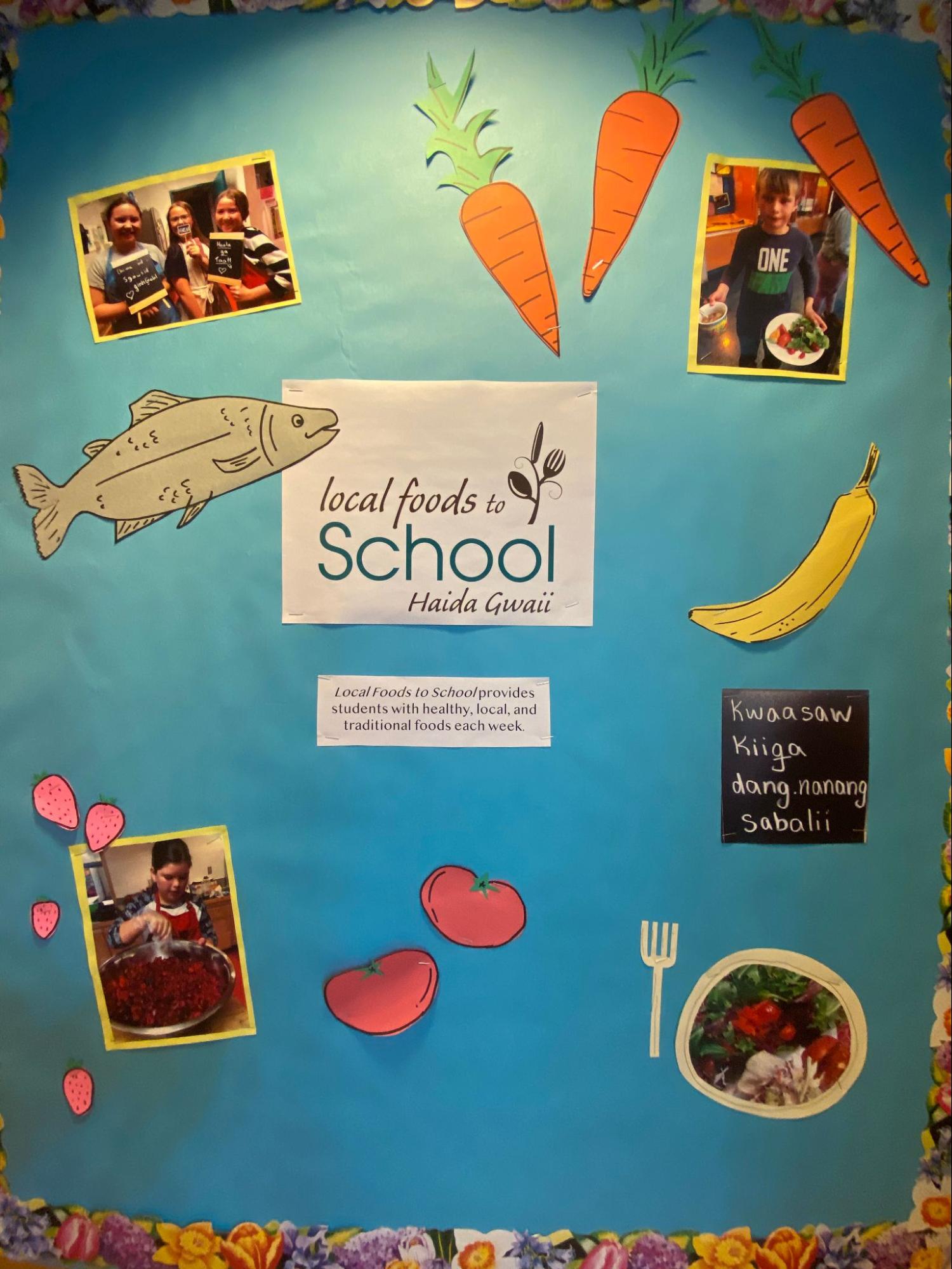

Sian Nalleweg is a recent graduate with an Early Childhood Education; Diverse Abilities Educator Diploma and is working one on one in an Education Assistant role for School District 50, Haida Gwaii. She is a food champion, land protector, and passionate advocate for children’s rights. She is a member of the Early Childhood Educators of British Columbia, The Canadian Child Care Federation, and Vice President of her local CUPE union. Sian shares: “My family means everything to me, and if you don’t find me at work, you can find me at the beaches and the forests surrounding my home with my family.”

F2CC believes it is essential for children and youth to have an opportunity to connect with their food and understand where the food comes from. The connection between children, their food and their food system also extends to the connection to the land and the waters. It is critically important for children to learn about the land and their relationship with it, to explore their responsibility to the land and to consider how their own lives and health are interconnected with it.

Many educators also have a deep interest in learning more about land-based learning and how to embrace it in a respectful way – a way that’s appropriate and not appropriating. F2CC, through its Nourishing Relations initiative, is looking at how their operations can better honor and amplify Indigenous voices and this conversation is a piece of this work.

The following are some of the key moments that we took from the conversation:

Alan: When you take kids outside something changes in them; there is something quite grounding about being outside. It starts with our relationship with the land. It’s our responsibility to understand where our food comes from. If we learn how to learn from nature, if we learn how to look and we learn how to listen and slow down, that’s really a valuable and rich, rich lesson.

Daemin: Land-based learning is about learning from the environment and just getting outside. That’s a kind of learning that you can’t get from a book or the internet or Zoom. It’s a different type of learning, where the land is teaching and the educators help facilitate. “Each day that I spend out there creates a fuller picture of my understanding of the world and myself in it, right?”

Sian: One of the facets for social and emotional wellness is the sense of “who am I?” This sense of identity is important for all children. Having a strong identity is instrumental in our ability to contribute as caring citizens and stewards to the land and waters.

Robbie: “This is decolonizing work happening!”

Sian: Educators have an important role to contribute to reconciliation. To meaningfully participate and contribute to a land-based approach is to be part of the transformative change. * See additional resources shared by Sian

Alan: There’s an awakening of reconciliation in the education system. An important lesson from Robin Wall Kimmerer’s book Braiding Sweetgrass is to see everything that comes from the land as a gift. If you see your harvest as a gift from the land then maybe we’ll learn to care for the land and love the land differently. “Reconciliation is the healing of the relationship with the people as well as our relationship to the land”.

Daemin: You can’t teach about land-based learning without talking about our disconnection as Indigenous people. Colonization has led to the breaking of us from our food system, our Elders, from our land, from our rights, from our resources. The wild rice called manoomin helps our people to find healing in themselves and to find healing with what’s been done to us. It’s really about connecting people to their identity and helping them learn who they are.

Sian: I work at Sk’aadgaa Naay Elementary School, a public school on a private reserve in Skidegate British Columbia that is surrounded by a learning forest, nearby beach access, a greenhouse, and a natural play space. Having these spaces supports the well-being of the children. My approach focuses on connectedness and a sense of place. To me, land-based learning is understanding that humans, creatures, plants, trees and non-living entities are all interconnected. It’s learning with the mind, body and spirit. The relationship with others and the environment is reciprocal and responsive.

Daemin: For me, land-based learning is a more sensory thing and she shares that all your senses are heightened when you’re out in nature. The smells are a major part of how I read the wild rice – its the readiness at each stage in the production, the way that it sounds as it falls into the boat – all things that I can talk about but aren’t really conveyed unless you’re experiencing them. Land-based learning is a fuller experience. At different stages of life, wild rice taught me different things: learning how to work hard, giving me purpose or direction.

Alan: It’s important for school to reflect “who we are”, and for Indigenous people this is often not the case. Loughborough Public School, where I teach, worked with members of the Anishinaabe community to create a sacred rock circle and a grass dancer came and opened the circle and taught them. That’s part of my approach – helping school to be meaningful, empowering and to reflect the many diverse cultures that are in the room with us. I teach how the students can create meaningful change. We can’t change history but we can make tomorrow better.

Loughborough has been identified as a Legacy School by the Downie Wenjak Foundation for their work towards Truth and Reconciliation.

Daemin: The earlier you can connect kids or people to their food, the earlier they can start caring and when they start caring young it carries with them through their life and it’s an advantage for them. Everybody can care about where their food comes from!

Sian: Living on an archipelago, Haida Gwaii is very dependent on the ferry and the weather. So it is even more important to have these teachings and food security already in place for the children and for the new generation.

Alan: You don’t have to know it all! If you are non-Indigenous, you need to ask people who do know and invite them in. All the initiatives that were put in place in Loughborough Public School were in partnership with Indigenous leadership from within the community. You need to have a lot of humility and be ready to say “let’s learn this together”.

Daemin: Anybody can reach out into nature or get something from the environment. You have to be patient; Knowledge Holders or Keepers are hard to seek out at times. So don’t come looking for answers in a day! It’s gaining meaning from little bits at a time. Use tobacco (Semaa) as an offering if you are seeking Indigenous people’s advice. “Semaa is the one plant that remembers how to speak between everything and that is why Indigenous people use it, it’s to speak your intention and your will so that there’s not a miscommunication.”

Loughborough’s sacred rock circle is an outdoor teaching space.

Sian: Bring everyone together – all human beings back into relationships. Seek out your Indigenous Knowledge Keepers. Invite the families to contribute. Find support in your school districts and use the strong webs of community that have been caring for children for millennia.

Sian: Connect with your Indigenous communities! Experience cultural opportunities. Join in any professional development that was created by Indigenous educators. Join meetings. Mourn with the community. Collaborate with colleagues. Listen to many Elders, leaders, and celebrate historical events. Learn to speak some of the local Indigenous language to speak to Elders and children. Come with an open mind!

Alan: Starting locally is really important with your own community. You also have to recognize the diversity of Indigenous people across Turtle Island and “definitely don’t be afraid to try, to make mistakes. Forgive yourself, ask for forgiveness and move on and keep on learning!”

Daemin: Anybody can start land-based teaching just by going outside and following a desire and curiosity to learn. The more time you spend outside, the more you learn. “In the fall, when I get out there to do wild rice on a regular basis, I feel like I have way more life going on.”

Alan, Daemin and Sian closed by reflecting on the interconnectedness of the world. You can think of the forest as a group of people who are holding each other’s hands under the soil!

Thank you to Alan, Daemin, Sian and Robbie for such an insightful conversation!

Access a video that Sian shared about Orange Shirt Day this year at the school where she works. As shared by Sian: Dang gwa ‘laa Sian the song is the Sk’aadGaa Naay Song that was potlatched and became the intellectual property of Sk’aadgaa Naay Elementary School in 2009. The song is sung by Erica Reid.

Multilingual WordPress with WPML