On March 2nd, 2022, the Edible Education Community of Practice hosted a conversation to explore ways to incorporate Indigenous plants and ways of knowing into teaching gardens, and heard about examples from two educators. In order to continue the conversation from the November webinar about Land-Based Learning, two guest speakers shared their experiences:

- Lori Snyder, a Métis herbalist and educator with a deep knowledge of wild, medicinal and edible plants that grow in everyday spaces, Lori leads people of diverse backgrounds in reconnecting to the Earth’s wisdom. Lori is a descendant from the Powhatan, Dakota, T’suu tina, Nakota, Cree, Nipissing, Dene and Anishinaabe peoples, mixed with French and Celtic ancestry. She joined us from the unceded land of the Musqueam, Squamish, and Tsleil-Waututh peoples (Vancouver, BC) where she works with K-12 students.

- Tristan Landry, a professor at the Université de Sherbrooke, where he teaches contemporary European history, joined us to share his experiences working in the historical garden of the university. Tristan is of Acadian and French descent and joined us from the land of the W8banaki, the Ndakina. K’wlipaï8ba W8banakiak wdakiw8k (Sherbrooke, QC).

Part 1 : The Université de Sherbrooke’s historic garden, presented by Tristan Landry

As a specialist in the history of food, Tristan offered a seminar a few years ago that took the form of an ancestral cooking class. The students were so passionate that they wanted to go further: This is where the idea of creating a historical garden was born, in 2018. After visiting other historic garden designs, Tristan and his students created a French settler garden and a Indigenous garden. In this one, they used ancestral seeds and traditional techniques such as the synergistic cultivation (companion planting) of squash, corn and beans (Three Sisters garden). From the beginning, the harvests have been incredible.

Tristan really wanted to develop collaborations with speakers from different Indigenous communities. So the first year, he invited a friend to come and cook what they had in the garden outdoors. The following year, an Waban-Aki (Abenaki) woman who has a catering service in the area came to cook with the students using the crops from the garden. Each time, these events were a great success, both with the students and the local media.

In the third year of the historical garden, Tristan wanted to add an herbal medicine cultivation bin. The idea was to teach students about Indigenous medicinal plants, such as swamp myrtle, sacred tobacco and St. John’s wort, through cultivation. The students worked to popularize the medicinal uses of these plants through interpretive signage in the garden and the creation of the Jardin Historique website. It lists all the plants that have been cultivated and studied in the garden, with a precise explanation and drawings. They have recently gone one step further by creating a web application named “Uiesh” that strives to identify every initiative related to Indigenous history in the province and beyond, such as museums and gardens. Tristan is thinking about continuing to develop other historical gardens at the Université de Sherbrooke to promote land-based learning, such as a Viking garden.

Part 2 : Presentation of Lori Snyder

When the organizers asked Lori to share some of the points that she spoke to during the event, she shared the following ideas for educators:

How do we decolonize our garden and minds and bodies? One school in Vancouver converted a field into a medicine wheel garden, growing plants like flowering red currant (that the hummingbirds enjoy), peppermint, calendula, bleeding heart, dandelions, Nootka rose, and more. When we grow more than just vegetables in our gardens, we see life like insects and birds benefiting from our stewardship of the land. To learn more about pollinators, check out this Victory Gardens for Bees book by Lori Weidenhammer, who worked with Lori Snyder on school gardens in Vancouver.

When designing a garden or bringing students onto the land, encourage them to think about: What are the purposes of these plants? What are their gifts? Why are they here? With these questions, we can think about reciprocity, and cyclical relationships with the land.

Suggested activities to do with students/youth:

- Create a herbarium (a collection of dried plants); responsibly collect samples of different plants, and have students study them. Students can draw pictures of them, do leaf rubbings, look at the details of the plants, and share what they see/smell/taste.

- Share the herbarium drawings along the school fence (see photo).

- Journal – What are we witnessing today? Look at the sun, wind, shadows, or water.

- Share what our favorite foods are, and research their origins.

- Write poems or songs about the land, and share gratitude for the land.

- Compare plants to the Doctrine of Signatures, and learn about how often how the plant looks corresponds to the part of the body it is used to help heal (e.g. walnuts and the human brain)

- Get to know a dandelion! Dig one up, taste the leaves, roots, and flowers.

The school yard is an extension of the classroom, so there is a lot of meaningful work that happens there. Remember that you can observe, witness, and listen (OWL) when you are outside. For example, count the species of plants (Indigenous to the area, introduced, invasive plants), look for insects (Who is it? Who is eating it? What is it doing?), look for birds (Who is it? What does it sound like?), and notice the weather (sun, wind, and precipitation).

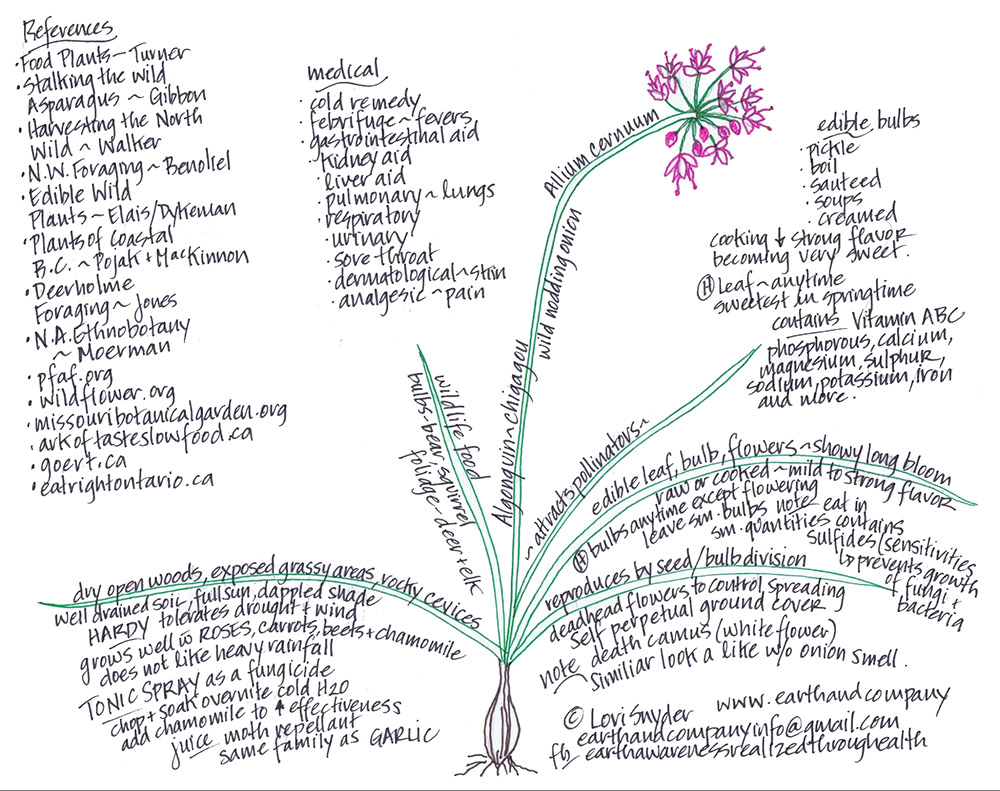

The nodding onion is a really interesting plant to look at with students, and you find more details about it on the drawing below:

- Bulb – Highly prized food during potlatches

- Flower – Good for pollinators

- Seed – Easy to collect and spread

- Leaves – Tasty for students to chew on

Conclusion

Breakout Groups

At the end of the webinar, participants met in breakout groups to share what they had learned from the presentations, and to discuss what they would like to bring to their own teaching gardens.

A Few Reminders

- The historical garden reminds us of the undeniable contribution of Indigenous peoples to our agricultural and plant heritage as well as the numerous traditional knowledge that exist among First Nations.

- Research native plants to your area and strive to include them in the garden, alongside your fruits and vegetables if you like.

- With students, explore the school yard and see what native plants are already naturally found there.

- For more information about Indigenous gardens and lesson ideas, visit Farm to School BC’s Learning from the Land Toolkit; Lori Snyder inspired the Lesson 4: Native Plant Walk.

For more information on the presentations, visit the Université de Sherbrooke’s historic garden website, or contact Lori Snyder through her website.

To watch a video of the call, visit this link, for English.

Decolonizing Your Garden webinarPasscode: mAb6.@cn